Behind the Scenes at a VC Fund, Part 2: Helping Founders and Time Allocation

VCs have 3 principal jobs: picking startups to invest in, helping startups after investing, and raising capital for investing. Each of these jobs will be covered in its own post. This post, the second in the series, focuses on how VCs spend their time (charts and graphs included!), and how they help the companies they invest in.

Table of Contents

Part 1: Deals, Deals, Deals

A post on how VC funds source, analyze, and choose companies to invest in.

Part 2: Helping Founders and Time Allocation [this post]

Basic Terms

Why do VCs Help Portfolio Companies?

How Much do VCs Help Portfolio Companies?

Ways that VCs Can Help

VC Time Allocation

Meetings

Email

Research

Events

Part 3: Fund Structure, Fundraising, Investor Relations, and FAQs

A post on the basic mechanics of how VC funds are structured and raised, how VCs interact with their own investors, and venture capital FAQs.

Basic Terms

Portfolio Company – a company that the fund has already invested in.

Limited Partners (or LPs) – a fund’s financial backers. These are the people whose capital is being invested. LPs can range from university endowments to pension funds to wealthy individuals.

Why do VCs Help Portfolio Companies?

Most good VCs try to help their portfolio companies for several reasons:

If VCs are helpful, founders will recommend them to other founders.

Being helpful can materially increase the value of a company – and by extension, the value of the VC’s investment. For example, let’s say my fund owns 10% of a SaaS startup. That type of company tends to trade at 5x revenue multiples in the public stock market (e.g. $200m in revenue -> $1b valuation). If I introduce that company to 10 customers that create $1.5m of additional revenue, then the paper value of my portfolio goes up by $750k (= 10% ownership x $1.5m revenue x 5.0 revenue multiple).

On a more human note, most VCs prefer to think of themselves as company advisors rather than money managers. This often results in VCs wanting to help just so that they feel useful. (The downside here is that if a VC can’t be useful but tries anyway, they just get in the way.)

How Much do VCs Help Portfolio Companies?

Motivations aside, the level and frequency of engagement vary greatly from investor to investor. Here are the levels that I’ve observed:

Uninvolved. The investor writes a check and then you never hear from them again.

Passive. The investor doesn’t reach out proactively, but invites you to ask them for help when you need it. Sometimes these “let me know if I can help” offers are lip service, and sometimes they’re genuine.

Semi-active. Most founders send monthly update emails, and these emails often have an Asks section that lists areas where investors and advisors can help. Semi-active investors will respond to those asks when they have something to offer. Here the founder is not asking for help one-on-one, but they still have to ask.

Active. Active investors will reach out proactively when they have something they can offer (like a potential engineering candidate or an intro to a customer). They’re often thinking about ways to help in the background, even if founders aren’t explicitly asking them to.

Very active. The next level of engagement typically involves a regular meeting cadence – sometimes as often as weekly, but more commonly every 3-6 weeks. At these meetings, which are almost like informal board meetings, founders will talk about how their business has been going for the last few weeks. As the VC listens, they’ll ask probing questions – both to understand the business better and to help the founder clarify their thinking – and suggest ideas or improvements or potential intros. For example, a founder might talk about how their recent experiments with Facebook ads aren’t going well. The VC will ask about the experiments, and based on the answers might offer an intro to a Facebook ads expert, or recommend a marketing channel that has worked better for other similar companies.

Board level. Board level engagement is a more formal version of the “very active” level. The VC and founders often work together for multiple hours every month, and sometimes every week. For active board members, working with a single company might represent 5% or even 10% of their total work hours. This is why most later stage VCs top out at 8-10 simultaneous board seats.

While the level of involvement varies across investors, generally the more capital a VC is investing, the more involved they will be. That said, there are large funds that are very passive and small angel investors that are very active.

Ways that VCs Can Help

As I wrote ~3 years ago, good investors can help in many ways. In practice, the most common areas where VCs help are:

Intros to prospective customers, job candidates, advisors, service providers, other investors, etc.

Comparables and benchmarks for running your business, including compensation benchmarks, business benchmarks (e.g. typical churn levels or salesperson commission structures), and office space comps.

Feedback on website copy, sales and marketing materials, product UI/UX, etc.

General business advice, including tips for hiring execs, fundraising, choosing KPIs, and so on.

Interviewing and helping to close key job candidates. Sometimes talking to a VC gives an on-the-fence VP the push they need to join a startup.

High level strategic guidance. Experienced investors have watched 10+ or even 100+ companies grow (and struggle), and they can see early signs of challenges of opportunities. Sometimes the most valuable aid an investor can offer is explaining what’s likely to be around the corner in 6-12 months at a time when the founder is spending most their time thinking about tomorrow or next week.

As a meta-observation, founders have knowledge that’s deep but narrow while investors have knowledge that’s shallow but wide. Investors understand common patterns of success and failure across many types of businesses, but chances are they know very little about a specific business or industry. Founders on the other hand know a ton about their specific business, but haven’t had a chance to see what does and doesn’t work across many companies. As a result, VC advice is often most valuable when it’s applicable across many companies, but founders are probably wasting they’re time if they’re asking a VC for specific SEO tips or how to sell to plant managers in the Oil and Gas industry.

VC Time Allocation

As a VC, I spend most of my time on meetings, email, and research. I analyzed data from Google Calendar and Gmail on where my time went over the last few months, and the results are described in the remainder of this post.

Meetings

VCs meet with founders, service providers, LPs, other VCs, job candidates for portfolio companies, and many other parties. To give a sense of how those meetings break down, I categorized and logged all of my meetings for May, June, and July of this year.

Here’s how most of the days feel:

Here’s the average number of hours of meetings I had by weekday:

My office is in San Francisco, but I live 25 miles south in Redwood City. If you’re wondering about why Tuesdays and Fridays seem so much busier than others days, it’s because those are the days I usually spend in SF. Somewhere in here is an observation about how most Silicon Valley startups are moving out of the peninsula and into SF.

Here’s the distribution of hours of meetings per day:

Most days had 3-6 hours of meetings, although there were outliers on both sides.

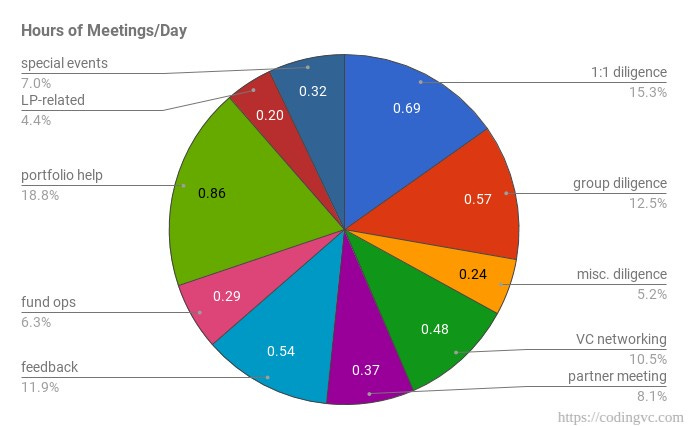

Here are the types of meetings I had:

Clockwise from the top right, the categories are:

1:1 diligence – one-on-one pitch meetings (or calls) with founders of potential investments (3.5 hours/week)

Group diligence – full team pitch meetings (or calls) with founders of potential investments (2.75 hours/week)

Misc diligence – other diligence-related meetings for prospective investments: founder reference calls, customer reference calls, legal work, and so on. (1.25 hours/week)

VC networking – meetings with other VCs. These meetings are with earlier stage investors (whose companies I might invest in in the future), similar stage investors (whom I can partner with on new investments), and later stage investors (whom I can introduce to my existing portfolio companies). (2.5 hours/week)

Partner meetings – internal meetings where the fund’s partners discuss ongoing action items: decisions and next steps on new investments, ideas for helping existing portfolio companies, hiring decisions, upcoming events, and so on. (1.75 hours/week)

Feedback meetings – meetings with founders who are not currently fundraising, but are looking for feedback on their idea/business plan/pitch in preparation for a future fundraise. (2.75 hours/week)

Fund operations – miscellaneous meetings related to running the fund: interviewing candidates, talking to service providers, event planning, team off-sites, etc. (1.5 hours/week)

Portfolio help – meetings that help portfolio companies in some way: brainstorming sessions with founders, interviewing key job candidates on their behalf, helping them prepare for the next funding round, and so on. (4.25 hours/week)

LP-related – meetings with current and potential investors for our fund. (1 hour/week)

Special events – various dinners and demo days. (1.5 hours/week)

The chart shows that about 33% of my meeting time is spent on diligence, 22% is spent on networking with VCs and founders who are not fundraising, 19% is spent helping portfolio companies, 19% is spent on internal fund work (partner meetings, hiring, LP updates), and 7% is left over for special events. On average, I have about 23 hours of meetings every week.

Email

According to Gmail Meter, I receive 2,000 emails and send 1,000 emails in a typical month. If you assume it takes 1 minute to read a typical email and 2 minutes to write one, this represents about 15 hours of email time every week.

Research

Many of the meeting categories above require doing some work before and/or after each meeting. For example, I spend about 15 minutes preparing before every 1:1 diligence meeting. If the meeting goes well, I’ll spend 30-60 minutes doing research and typing up notes for the other partners in my fund. If the meeting doesn’t go well, I’ll spend 10-20 minutes writing a nice email to the founder that explains why I’m passing on the investment opportunity.

Events

The last part of my job revolves around occasional special events. These include things like Y Combinator’s biannual Demo Days, which are 3-day events where 100+ founders pitch their companies to investors. My schedule fills up for 1-2 weeks before and after each of these demo days.

My fund also puts together an annual LP day for our own investors, and an annual founder/investor retreat. Both of these take weeks of planning and preparation. These types of events only happen a few times a year, but when one is coming up it doubles my workload.

Conclusion

This post talked about how investors engage with portfolio companies and how VCs† spend their time. The next and final post in this series will talk about how venture funds are structured and how VCs work with their own investors.

† By “VCs” I mean “me,” because that’s the only VC that I have lots of data for.