I’ve now been a VC for almost eleven years. While most of my investing career was focused on B2B SaaS investments at Susa Ventures, two years ago I started pivoting into deep tech investing1 via our new fund, Humba Ventures. As I started investing in areas like robotics, energy, biotech, and defense, I tried to learn more about their historical performance.

Since I’m an engineer and data guy by training (and since I’m betting my career on these categories!) I decided to dig into some PitchBook data2. This exercise convinced me that deep tech is the best place to invest and build right now, and that the following four assumptions about deep tech companies turn out to be misconceptions:

Deep tech companies have poor outcomes.

Deep tech companies are much more capital intensive.

Deep tech companies take much longer to exit.

Deep tech companies have much higher failure rates.

The rest of this post covers each of these points in detail.

Do deep tech companies have good outcomes?

Yes!

Many deep tech industries are huge, and there’s a lot of room for new players: batteries ($100b market), pharma ($1.5T), defense R&D ($150b in the US), industrial and warehouse automation ($200b total), and so on.

To take defense as a concrete example, this site lists awarded defense contracts. The DoD awards multiple 8-9 figure contracts daily. Any startup that captures just a few contracts of this size is basically a $1b+ company.

To get more specific, here’s a sample of great exits from just the past five years:

- 10x Genomics ($4.7b, gene sequencing tech)

- Archer Aviation ($1.7b, electric aircraft)

- Auris ($3.4b, surgical robots)

- Cylance ($1.4b, antivirus)

- Foundation Medicine ($5b, genomic profiling)

- IONQ ($2.3b, quantum computing)

- Luminar ($1.5b, LIDAR)

- Mazor Robotics ($1.6b, surgical robotics)

- Nextracker ($9b, solar panel positioning)

- Nuvia ($1.4b, chipmaker)

- Planet Labs ($2.8b IPO, satellite imagery)

- Quantumscape ($3b, lithium battery developer)

- SentinelOne ($5b, security platform)

This doesn’t include many valuable still-private companies like Anduril ($10b), Locus Robotics ($2b), Redwood Materials ($5b), Relativity Space ($4b), Solugen ($2b), and, of course, SpaceX ($150b).

I think we’ll continue to see more and bigger outcomes in these spaces in the next few years. Many industries and problems could benefit from deep tech innovation, and either have no incumbents or old incumbents. For example, ABB is a leader in industrial automation ($30b annual revenue). It’s also a merger of two companies founded in the 19th century. It feels unlikely that in the next decade, the best entrepreneurial minds from SpaceX, OpenAI Microsoft, Tesla, etc., will be unable to make inroads against ABB’s market leadership.

Aren’t deep tech companies much more capital intensive?

On average, no! Lists of “most funded companies” are almost exclusively more traditional startups in areas like marketplaces, fintech, social networking, etc. These are companies like Uber, WeWork, and Oscar, which spend orders of magnitude more than most deep tech businesses.

Here’s a summary of PitchBook data for US/Canadian companies founded since 2010 that have had $250m+ exits3:

My analysis found that companies across traditional and deep tech sectors are similarly capital intensive. The median company has raised 11-15% of its exit size in prior funding, which runs counter to the common assumption that to get a $1b exit in deep tech, you need $500m+ in funding. Reasons for deep tech companies being less capital intensive than expected are an increasing abundance of grants and other non-dilutive funding, less competition for new customers, and larger contract sizes.

The table above also reinforces that there are many meaningful exits across all of these categories. They are all good territories for founders and investors to explore!

Don’t deep tech companies take much longer to exit?

The table above shows that the deep tech and life science companies actually exit 10-25% faster than their traditional counterparts. For example, the average company age for exits above $500m is just under 8 years for traditional companies, just over 7 years for deep tech companies, and under 6 years for life science companies.

My hypothesis is that deep tech companies that build valuable IP can have meaningful exits quickly, while traditional tech companies rarely have very strong IP and are mostly acquired based on great traction. It often takes longer to get to meaningful traction than to accumulate valuable IP.

(On a side note, this is why deep tech VCs value strong founding teams even more highly than traditional VCs: if the team is good enough to produce unique, valuable IP, then it’s likely to have a good exit.)

Isn’t the failure rate especially high?

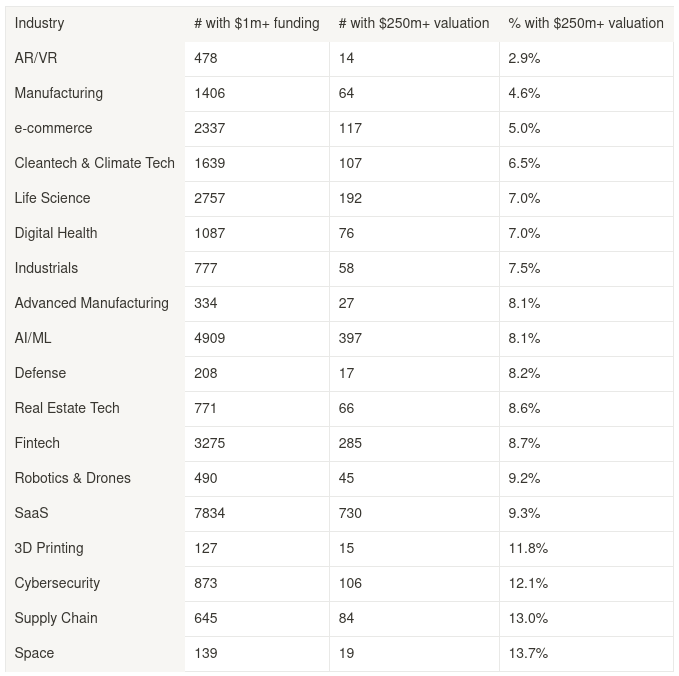

For me, this was the most interesting area to dive into. I got data across about 15 sectors for companies started since 2010 and with at least $1m in VC funding. My goal was to estimate the chance of a company with at least some VC funding eventually reaching either a $250m+ valuation or a $250m+ exit. I picked $250m as the threshold because that is already a good outcome, and at higher levels like $1b the data gets too sparse.

Here’s a table of industries, and the relative frequency of $250m+ valuations given at least some VC funding:

This table is sorted by the odds of hitting $250m+, and you can see that most categories are in the 7-9% range, with a few outliers on both sides. Deep tech sectors fare quite well here (except for AR/VR 😢). Basically, almost regardless of category, your chance of hitting a $250m+ valuation is around 7-9%.

Of course valuations are secondary to exits, so here’s a table of relative frequencies of $250m+ exits in each category.

Here deep tech actually dominates traditional tech. Companies in areas like defense, space tech, and life sciences have 2%-5% odds of having $250m+ exits, while companies in categories like SaaS, Fintech, and AI/ML have 1%-1.5% odds.

If you look carefully at the table above, you might notice that the odds of good exits in deep tech categories are often higher, but the number of good exits in these categories is lower. I think that’s a hint about why these companies tend to be more successful. Building a deep tech company is hard. Really hard. You typically need a multidisciplinary team that’s exceptional in multiple areas, and that’s a very high barrier to entry. But if you can assemble such a team then you will have much less competition than most startups and a higher chance of a good outcome.

For example, we recently invested in Antares, which is developing nuclear microreactors for defense applications on earth and in space. A good team for a company like this needs to know how to build reactors, how to sell to the defense department, how to deal with regulations, and so on. It’s very hard to assemble a team like this, and that’s why there are only a few microreactor startups. If you’re good enough to enter the space and get funded, you’ll be one of 1 or 3 or 10 companies fighting for market dominance, not one out of 500. This leads to better expected outcomes for the founding teams that are strong enough to get funded in the first place.

Key Takeaways

To summarize the data above:

There are lots of $1b+ deep tech exits.

While the absolute number of strong exits is smaller than for traditional sectors like B2B SaaS, the rate of good exits is approximately 2x higher.

Good exits for deep tech companies, on average, come 6-24 months sooner than good exits for traditional tech companies.

Deep tech companies, on average, have similar capital intensity to traditional tech companies. Across all exits above $250m, the average amount of capital raised is about 11-15% of the sale price regardless of sector.

Finally, while this post focuses on the financial performance of deep tech companies, investors and founders should also consider the opportunity to have a monumental impact on the world. Most startups are highly impactful on some group of people, and for deep tech companies both the impact and the size of the group tend to be much larger. Now is a better time than ever to build deep tech companies: off the shelf technology keeps improving, there are lots of funding and grant options, there are many successful deep tech companies to poach talent from, and macro trends like reshoring provide strong tailwinds for ambitious ideas.

If you’re building or investing in these spaces, please reach out! I’m leo@humbaventures.com, and our fund Humba Ventures is investing $250k-$500k in areas like energy, robotics, material science, and defense and aerospace.

Thanks to Julian Shapiro, Heston Berkman, Mike Annunziata, Mr. Exits, Jai Malik, Ian Rountree, Chelsea Goddard, and Josh Manchester for feedback on this post.

I’m using ‘deep tech’ loosely in this post. Our new fund Humba invests in deep tech companies (robotics, energy, material science, hardware, etc) and in critical national sectors (manufacturing, defense, education, etc). Many companies in our portfolio fall into both buckets.

Two caveats on Pitchbook: 1) they don’t allow their data to be published, so unfortunately I can’t share the raw data. 2) their data is good but not perfect, so the analyses in this post are meant to be directionally useful, and not 100% precise.

The PitchBook queries for this analysis were companies started since 2010, HQ’ed in the US or Canada, and either Traditional Tech (HealthTech, Digital Health, Supply Chain, Mobile, E-Commerce, SaaS, Big Data, Marketing, Artificial Intelligence, FinTech, InsurTech), Deep Tech (Robotics, Industrials, Manufacturing, 3D Printing, Cybersecurity, CleanTech, Space, Advanced Manufacturing) or Life Science. Life Science got its own column because it’s such a huge category when it comes to both funding and exits.

Great post! Seems like AI could have gone either into deep tech or traditional. Certainly some companies doing AI research like DeepMind, OpenAI, etc may be deep tech but the lack of granularity of Pitchbook date would make parsing those out super difficult!

Great data analysis! The list of successful exits in the last five years is compelling, debunking the idea that deep tech companies are more capital-intensive or take longer to exit.