The Fight Against Overconfidence

A few weeks ago, I wrote about the 100-hour rule:

For most disciplines, it only takes one hundred hours of active learning to become much more competent than an absolute beginner.

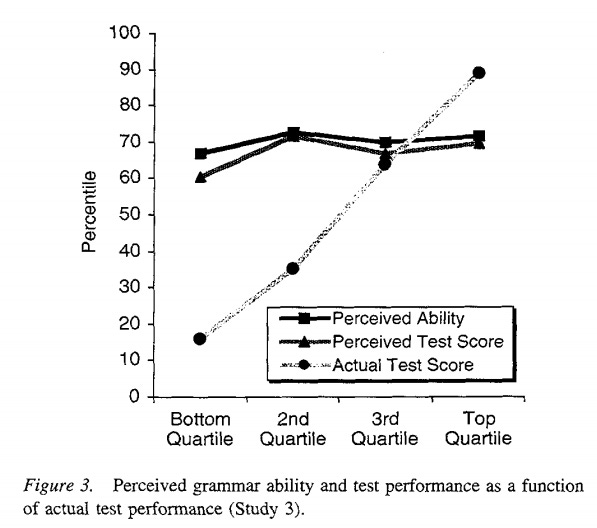

The downside of achieving basic competence is that it often leads to overconfidence. This is called the Dunning-Kruger effect. In a study published in 1999, David Dunning and Justin Kruger found that unskilled individuals greatly overestimated their abilities, while highly skilled individuals underestimated their abilities. Here’s an illustrative figure from the study:

The figure above shows that regardless of actual skill level, most people consistently perceived themselves as slightly above average. This is a gross underestimate for an expert, and a gross overestimate for a newbie.

The Danger of Overconfidence

Founders and VCs are often on the overestimation side of the curve. This is especially true when entering new industries or assuming new job roles. For example, a technical founder who does a few dozen sales calls might start feeling like they’re good at sales. Similarly, a VC who understands a specific business model in the context of a single industry may start believing that they understand that model in other industries.

This kind of overconfidence can be very dangerous. Some examples that I’ve seen firsthand:

An investor had some great investments in the past. They assume they have the Midas touch and confidently make new investments in areas where they have little experience. These investments turn out to be terrible.

A founder successfully built a company in the past. The founder assumes they have the recipe for success, so they try to replicate the same formula in a new industry that follows different rules. Predictably, the company fails.

An investor watched a business model fail in the past. Consequently, they start avoiding other companies with a similar business model, thereby missing out on great opportunities.

A technical founder handles sales in the early days of company and closes a few sizeable contracts. As a result, the founder believes that they’re great at sales, and postpones hiring an experienced salesperson who actually knows how to sell. (This example is more insidious because the founder may actually be okay at sales, but they don’t realize just how much better an expert would be.)

An investor watched a specific decision lead to a company’s demise in the past. That investor now warns every company against making the same decision, regardless of context.

All of these are mistakes that come from overestimating what one knows and underestimating what one doesn’t know.

The Danger of Being Unreceptive

The downside of overconfidence is frequently compounded with being unreceptive to advice and feedback from others. This is basically generalized overconfidence: instead of believing you are right about everything in some field, you believe you are right about everything. This is a common trait among founders who think they’re the Steve Jobs of their industry: they think they have the right plan to build what the market needs, and they refuse to change that plan based on feedback. This is usually fatal to a company. If you have to choose, it’s much better to be overconfident but receptive than appropriately confident but narrow-minded.

Being receptive to advice is critical for founders because they have to get so many things right when building a company. Who should be on the founding team? Which tech stack should be used? What features should the MVP include? What’s the right go-to-market strategy? How should sales and marketing be handled? Eventually, all of these questions have to be answered well. Starting with good answers to 40% of the questions and iterating toward 100% based on feedback is much more likely to lead to success than starting at 80% and being stuck there due to closed-mindedness.

A Healthy Amount of Confidence

What can one do to overcome the dangers of overconfidence and unreceptiveness? Here are four concrete ideas:

Interact with amazing people as much as possible. Discuss and debate with people who you think are smart. Listen to experts in skills likes sales or domains like SaaS, and get their feedback and advice on what you’re doing. Even if you consider yourself an expert, it doesn’t hurt to see what other experts think. (Note: interactions don’t have to be in-person; they can be online, or one-way through reading books or blog posts or tweets.)

Delegate responsibility and resist the urge to micromanage. Overconfidence entices us to do everything ourselves, but there are only so many hours in the day. Can you be the CTO and VP of Sales at a startup? Sure – at a 1-person company. And maybe even at a 5-person company. But probably not at a 20-person company, and definitely not at a 1000-person company. If you know you’ll have to delegate at some point in the near future, consider delegating a little earlier than you’d like.

Focus your time on areas where you have the greatest comparative advantages. If you’re a 10x engineer and a 2x salesperson, and your cofounder is a 3x engineer and a 0x salesperson, then it makes sense for you to do sales in your company’s early days. But, as soon as reasonably possible, hire a real salesperson. If you’re a 10x engineer, you should be writing software, not calling prospects. If you focus on the areas where you’re strongest relative to everyone else, you are naturally forced to delegate everything else to other people and to trust them to execute.

Write down all feedback. You don’t have to act on it right now. Over time, if the same comments keep coming up, you might need to re-evaluate your plans. This is similar to how 37signals does feature prioritization:

Every new feature request that comes to us – or from us – meets a no. We listen but don’t act. The initial response is “not now.” If a request for a feature keeps coming back, that’s when we know it’s time to take a deeper look. Then, and only then, do we start considering the feature for real.

Getting Real, p. 57

Above all, be humble. The most successful people are rarely the ones who believe they know everything.